This was no ordinary trial.

It was unusual in its sheer scale: more than three years of police work; 42,000 pages of crown evidence; seven months of hearings; up to 18 barristers in court at any one time; 12 defendants facing allegations of crime spreading back over a decade.

But what made it most unusual was what it represented. First, this was a long-delayed showdown between the criminal justice system and parts of Fleet Street, in which the reputations of both was at stake. Beyond that, however, this was a trial by proxy, in which Rebekah Brooks stood in the dock on behalf of a media mogul and Andy Coulson acted as avatar for the prime minister, with the reputations of Rupert Murdoch and David Cameron equally in jeopardy. Officially, the trial was all about crime; in reality, it was all about power.

And just as the main players were absent from the court, so the real issues which for years had inflamed public opinion were not mentioned on the indictment – the perception that some news organisations were all too happy to invade privacy and ruin lives in order to sell more papers; that they regarded themselves as not only above the law but above the government, which would do their will or suffer for it; that they had poisoned the mainstream of public debate with a daily drip-feed of falsehood and distortion.

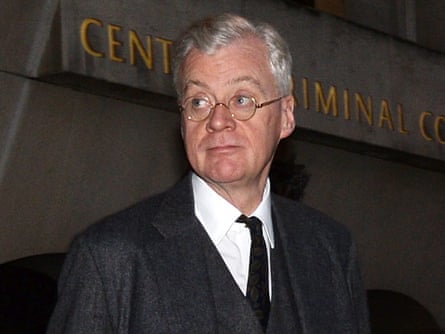

On the afternoon of 30 October 2013, as the prosecuting counsel, Andrew Edis QC, first rose to his feet, I looked across at the 12 jurors who had just been empanelled – mixed gender, mixed race, mixed age – and thought that they represented arguably the most ancient form of democracy (centuries older than the idea of voting); that this was the moment when all the wealth and influence of the Murdoch network finally confronted a form of popular will which they could not compromise. It was not as simple as that.

Somebody called it the trial of the century. That worked well enough as an indication of its scale and of the highly unusual status of some of those in the dock. But it was more accurate in another sense, that, as the weeks went by, this trial came to embody the peculiar values of this particular century – its materialism and the inequality which goes with it, the dominance of corporation over state.

The judge, Mr Justice Saunders, was outstanding – clever, considerate, surprisingly funny, displaying never a flicker of fear or favour towards the ambassadors of the power elite who sat before him in the dock. The jurors were a tribute to the jury system. Their facial reactions each day showed that their concentration scarcely wavered during the marathon (though one had the initially alarming habit of listening with her eyes shut). Often, they sent written notes to the judge which were extraordinarily astute, spotting glitches in the evidence which had been missed by every single one of the highly paid counsel in front of them. But ...

Rolls-Royce defence

Rupert Murdoch’s money flooded that courtroom. It flowed into the defence of Rebekah Brooks, because he backed her; and to the defence of Andy Coulson, because Coulson had sued and forced him to pay. Lawyers and court reporters who spend their working lives at the Old Bailey agreed they had never seen anything like it, this multimillion-pound Rolls-Royce engine purring through the proceedings. Soon we found ourselves watching the power of the private purse knocking six bells out of the underfunded public sector.

In the background, for sure, there was a huge publicly funded police inquiry, forced by the stench of past failure to investigate thoroughly the crime which had been ignored and concealed for so long. But when it came to handling the police evidence in court, Brooks and Coulson had squads of senior partners, junior solicitors and paralegals, as well as a highly efficient team monitoring all news and social media. The cost to Murdoch ran into millions. Against that, the Crown Prosecution Service had only one full-time solicitor attached to the trial and one admin assistant. They worked assiduously. One prosecution source said it was surprising they had not simply collapsed under the strain. The effect was clear.

Defence barristers would pause, turn and find a solicitor to feed them information while crown counsel often found an empty seat. The defence produced neatly laminated bundles of evidence, while the crown hastily photocopied material into files which sometimes proved to be incomplete.

Towards the end of the trial, Edis decided the jurors needed an electronic index to be installed on a computer in the jury room to help them find their way through the avalanche of paperwork which had descended on them. With the CPS struggling for cash, Edis offered to pay for it out of his own pocket, and, in the absence of CPS manpower, two junior crown counsels had to create the index themselves. Over and again, the defence teams had the resources to find some helpful stick with which to beat a potentially dangerous witness – a misremembered date, a forgotten detail, even on one occasion the fact that the witness had once had coffee with Nick Davies from the Guardian. So they were able to create complication, confusion, doubt.

An expert witness claimed to be able to track the movements of defendants by analysing their use of mobile phones: the prosecution failed to notice that his conclusions were contradicted by his own data; he was chopped to pieces by the defence and admonished by the judge. The jury was told that the News of the World had hacked phones to obtain a story about Paul McCartney having a row with his then wife Heather Mills and throwing their engagement ring out of a hotel window: the prosecution failed to take account of evidence in the possession of the police which indicated the paper had bought the story from someone who worked in the hotel.

These weaknesses were exploited by the kind of high-octane cross-examination which could raise reasonable doubt about whether the witness is breathing. (“When did you start this breathing? … You can’t remember?! … How often do you breathe? … You don’t know?!”). Here the disparity in funding was striking but not so important. There were masterclasses in the skills of advocacy from Edis as well as from some of those acting for those in the dock. It simply stuck in the craw that Edis was earning less than 10% of the daily fees enjoyed by some of his opponents.

Finally, the crown was hampered by the rules of court that allow it to make an opening statement but require it then to present items of evidence without any comment as to why they matter, a rule policed with ferocious efficiency by the Rolls-Royce defence teams. In a normal case, where the prosecution might spend only three or four days presenting its case, that would not matter: the evidence would be relatively simple; it would be clear how each piece fitted into a picture. In a seven-month trial, the rule combined with the crown’s scarce resources to produce a kind of chaos.

When Brooks’s barrister, Jonathan Laidlaw QC, rose to open her defence after nearly four months of prosecution evidence, he told the jury with his trademark combination of gentle delivery and vicious effect, that it had not been “the easiest case to follow”. The crown had jumped from topic to topic, he said. It had made “something of a mess” of timelines for the key hacking victims, which were incomplete and potentially misleading. It had flashed up documents on the courtroom screens and forgotten to give them to the jury: “If there is a sense of confusion about the evidence and what it is supposed to relate to, that would be entirely understandable … There are categories where we simply don’t know or understand the point that is being made.”

Unpredictable contest

It may have been patronising, but he had a point. The crown had spent months effectively throwing random bricks at the jury with little or no explanation as to how they fitted together. Laidlaw set about building the prosecution’s house for them, attempting to persuade the jurors that, when they saw it in its final form, they would see it was full of holes.

This is not to say that the defendants had no problems. In pre-trial hearings, Brooks lost her lead barrister, John Kelsey-Fry QC, because the former royal editor, Clive Goodman, said he wanted to call him as a witness to the cover-up at his own trial for hacking in 2007. The judge agreed to delay the trial for seven weeks while she instructed Laidlaw – and that meant Coulson lost his barrister, Clare Montgomery QC, because the new timing overlapped with a case she had to conduct in Hong Kong. The trial opened against a backdrop of public hostility to Brooks and Coulson, not only because of the high-profile hacking saga, but also because of their careers. Brooks’s lawyers tried and failed to persuade the judge to ban all trade union members from the jury on the grounds that they were bound to be antagonistic.

Throughout the trial, the defendants were thrown off-course as the crown, struggling to keep up, served new evidence that should have been presented before the trial started. Even as the final evidence was being put to the jury in April, the prosecution suddenly announced it had 48,000 email messages which the FBI had obtained from News Corp in New York; they had been with police in London for 16 months.

All this made the trial a peculiarly unpredictable contest. From the start, the crown case was weak, particularly against Rebekah Brooks. There was no direct evidence at all to implicate her in phone hacking. Indeed, there was simply a lack of any direct evidence about her of any kind. That was partly because of the passage of time: she stopped being editor of the News of the World in January 2003, so naturally paperwork and other evidence had been lost. Some had been destroyed. Over the years, News International had deleted some 300m emails from their systems, only 90m of which were retrieved, including only a handful from Brooks’ editorship. The hard drive had been removed from her computer for safe keeping then lost.

But there was no doubt at all that the News of the World had been involved in crime on a massive scale. Before the trial opened, three former news editors and the specialist phone-hacker Glenn Mulcaire had pleaded guilty to conspiring to intercept voicemails. By the time it finished, News International had paid compensation to 718 victims of the hacking – an average of nearly three agreed victims for every week during the five years for which patchy evidence of Mulcaire’s work has survived. Hundreds more alleged victims were still being identified by police.

Platform of inference

The hacking case against Brooks and Coulson was based on a platform of inference. How could they not have known about the beehive of offending around them, the crown asked. How could they not have known about Mulcaire’s speciality when he was one of only two outside contributors with a full-time contract and was being paid more than any reporter, at one point more even than the news editor? How could they not have known the origin of all those stories whose accuracy they had to test? How could they have been ignorant when a humble sports writer described Mulcaire, a former footballer, as “part of our special investigations team” in a story published by the News of the World when Brooks was editor? Brooks and Coulson insisted they had known nothing of Mulcaire’s criminality. They had not even heard his name until he was arrested in August 2006, they told the jury.

The attack on this platform of inference included a striking example of the impact of Murdoch’s money. The evidence which lies at the core of the hacking scandal is the collection of notes found by detectives when they first arrested Mulcaire in August 2006: 11,000 pages of his barely legible scribble and scrawl and doodle. The original police inquiry took one look at it and decided it simply did not have the resources to go through it all. When Operation Weeting in 2011 finally did the job properly, it took it the best part of a year. Brooks’s Rolls-Royce did it in three months and then had the resources to produce a brilliant analysis.

The notes showed that Mulcaire was tasked some 5,600 times during the five years that he worked on contract for the News of the World, an average of more than four for every working day. As a crude average, that would imply that between September 2001, when he was contracted to work for the paper, and January 2003, when Brooks left, he was commissioned around 1,400 times. But Brooks’s legal team set aside all those notes where it was not 100% certain they had been written during that time; and all those where it was not 100% certain that Mulcaire had been tasked to intercept voicemail as opposed to “blagging” confidential data. Since a considerable mass of his notes were incomplete and/or ambiguous on either date or task, this allowed Laidlaw to tell the jury that there were only 12 occasions when it was 100% certain that Mulcaire had hacked a phone while she was editor – an eye-catching point to be able to deliver in answer to the crown’s inference.

Where Brooks was concerned on the hacking charge, there was very little extra evidence to add to that platform of inference. Three witnesses came to court and recalled social occasions when she had discussed hacking with apparent familiarity. Brooks told the jury that she had read about hacking in newspaper stories; she had talked about it casually because she had not realised it was illegal; but she would never have sanctioned it because it was such a severe breach of privacy. One of these three witnesses – the former wife of the golfer Colin Montgomerie, Eimear Cook – was cut to pieces by a particularly destructive cross-examination.

Cook told the jury she recalled a conversation at lunch in September 2005, when Brooks had not only warned her that her own phone might be hacked but had described the ease with which it could be done. Cook added that during the same lunch, she thought Brooks had discussed the famous incident when she had been arrested for assaulting her then partner, the actor Ross Kemp. Laidlaw gently pawed her into position, confirming without doubt the date of the lunch, challenging the strength of her memory until she insisted she was absolutely certain and then, like Hannibal Lecter in a horsehair wig, softly and courteously, he cut out her heart: the incident with Kemp had happened six weeks after the lunch. Her story could not possibly be right.

Then there was Milly Dowler. This was almost spooky. It was the Guardian’s disclosure of the hacking of the missing Surrey schoolgirl’s phone that finally broke open the scandal. That was purely about the emotional impact of the story – that this was no celebrity victim, but an ordinary civilian, a child, and one who had been abducted and murdered by a predatory paedophile. Now, in court, once more, it was Dowler who presented the threat, not because of any emotional impact, but because it just so happened that this was the one example of hacking under Brooks’s editorship where there was some hard evidence. This was, as the judge said in a ruling, “the high point of the prosecution case”.

Having picked up a voicemail which seemed to suggest that Dowler was alive and working in a factory in Telford, the News of the World not only hid that information from police but later, when they had failed to find her, they contacted Surrey police and demanded that they confirm the story for them – and quoted the voicemail, in phone calls and even in email. The records of those calls and messages survived in the Surrey police archive. Brooks must have been consulted about the high-risk decision to hide information from the police, the crown argued.

She must have been told about this potentially huge scoop – and about its origin, they said. She must have known that seven journalists were working on it, including her news editor, Neville Thurlbeck, and her managing editor, Stuart Kuttner, who had both personally contacted Surrey police and quoted the intercepted voicemail. If it was not secret from the police, why would it be a secret from the editor? From the editor who was running a national campaign to protect children from predatory paedophiles?

Brooks’s answer was that she had been on holiday that week, in Dubai, and simply had not been told about any of this. Even here, the Dowler case proved special. She had been using a News International phone, and the itemised bill had survived in the company’s vaults. If she had been in London, there would have been no record of her conversations, but the phone bill showed she had called the desk occupied by her deputy, Coulson, for 38 minutes on the Friday of that week, as reporters crawled over the big story, and again for 20 minutes on the Saturday, as they pressed the police to confirm it. She had texted him too. However, the prosecution had failed to realise that the records of some of those calls and texts were linked to the time in Dubai, not London, a three-hour difference which allowed Laidlaw to pour justifiable confusion over the evidence.

In addition, she and Kemp had been joined on the holiday by a British tourist, William Hennessy, who told the jury that she had spent a lot of time on the phone, explaining on one occasion that she had to make a call “about the missing Surrey girl”. Hennessy was sure of the timing: he had bought a watch in Dubai and kept the receipt, which was dated. Brooks said she had no memory of that. She had remained oblivious to the whole saga, she said, even when she returned to the office the following week, never reading the story which the paper had published quoting the voicemail verbatim, never knowing that managing editor Stuart Kuttner was still hectoring Surrey police to confirm the tale. Kuttner, also on trial, was himself found not guilty of conspiring to hack phones.

Close to the action

Coulson always had more to deal with. While evidence of his three years as Brooks’s deputy was hard to find, there was a wealth of phone records, emails, voicemail recordings and Mulcaire notes about the hacking that happened when he was in charge, from January 2003 to January 2007. And Coulson had got himself dangerously close to the action.

Searching Mulcaire’s home and the News of the World office, police found hundreds of voicemails left by David Blunkett for his lover, Kimberley Quinn. Coulson startled the court by admitting that his chief reporter, Thurlbeck, had played some of them to him. He had then personally confronted the then home secretary with the allegation of his affair, telling him: “I am certainly very confident of the information ... It is based on an extremely reliable source.” Blunkett taped that meeting, and the tape survived. Coulson argued that this might show that he was aware of one instance of hacking but not that he was part of the conspiracy to make it happen.

Mulcaire then hacked the voicemail of a Labour special adviser, Hannah Pawlby, attempting to prove a false allegation that she was having an affair with the next home secretary, Charles Clarke. Coulson personally called Pawlby, saying he needed to talk to Clarke about “quite a serious story”. Mulcaire actually hacked his own editor’s message from Pawlby’s phone, and the recording was found by police when they searched his home. Coulson said simply that he wanted to talk to Clarke about a different story which was also serious; he had known nothing about the hacking of Pawlby’s phone.

When they were investigating Calum Best, News of the World executives feared that one of their journalists might be leaking information to him, warning him about what they were planning. Coulson sent an email: “Do his phone.” Mulcaire’s notes showed that he did then target Best, though it was not clear whether he succeeded in hacking his messages. Coulson said his email was an order to pull the itemised phone bills of the journalist who was suspected of leaking, to see if he had been calling Best.

Unlike Brooks, Coulson also faced two live witnesses who claimed he had known about the hacking. A showbusiness writer, Dan Evans, who had become a specialist hacker, told the jury that Coulson had hired him from the Sunday Mirror explicitly because of his hacking skill. He claimed that one day in the newsroom, he had played Coulson a tape of a voicemail hacked from the phone of the actor Daniel Craig in which Sienna Miller said she was in the Groucho club with Jude Law.

Coulson’s counsel, Timothy Langdale QC, a model of old-school courtesy built around a core of steel, released a swarm of questions around Evans. He stung him into describing his own criminality, his deal with the police, his history of cocaine abuse, finally pushing him into claiming to be sure of the date when he had played the Craig voicemail to Coulson – and then revealed that the editor had not been in the office on that day. When Langdale went on to query whether Miller and Law had been in the Groucho during that timeframe, the prosecution was left floundering: it had failed to get evidence from the club to prove their point.

Similarly, Coulson’s former friend and royal editor, Goodman, went into the witness box and told the jury that Coulson had personally approved his hacking of royal phones, for which Mulcaire was paid in cash with a false name and address on internal paperwork. He added that hacking was going on on “an industrial scale” at the time and was often discussed in meetings with Coulson until he banned any further open mention of it. Langdale pushed back hard, confronting him with evidence to suggest he had lied about the extent of his own involvement in the royal hacking.

Unheard evidence

A trial deals with only a limited amount of information, considering only the evidence which is available and also admissible and which relates directly to the charges on the indictment. As in any case, there was a great deal which the jury did not hear information which could have tipped their judgment for or against the defendants.

Some 30 News of the World journalists provided information which helped the Guardian uncover the scandal. But almost without exception, they spoke off the record. One of them – Sean Hoare – spoke openly, but he died in July 2011. A senior former executive and two of those who had pleaded guilty before the trial – Mulcaire and Thurlbeck – had discussions with the police about giving evidence for the prosecution. All three negotiations failed. Evans and Goodman were alone.

The jury heard nothing about earlier police inquiries into allegations of the News of the World’s involvement in blagging confidential records and bribing corrupt police for information, which occurred in the late 1980s and 90s. They heard nothing of the 3,000-word feature in the Guardian that described in detail the alleged involvement in this blagging and bribing of a senior executive from the paper. Similarly, they were told very little of the paper’s use of Steve Whittamore, who blagged information illegally, culminating in his conviction in court in April 2005.

The jury was told in detail about the information which Brooks said she had been given by an officer from the original inquiry, DCI Keith Surtees, who met her in September 2006 to tell her that her own phone had been hacked by Mulcaire. An internal email written at the time reported that, according to Brooks, police had found “numerous voice recordings and verbatim notes of his accesses to voicemails” and that they had a list of more than 100 hacking victims (as distinct from the eight who were later named in court) and that they came from “different areas of public life – politics, showbiz etc” (as distinct from the royal victims who were of interest to the only News of the World journalist they had arrested). This information was shared with Andy Coulson.

However, the jury was not then told of the letter which Brooks wrote to the media select committee in July 2009, after the Guardian first reported the true scale of the hacking, in which she said that the Guardian had “substantially and likely deliberately misled the British public”. Nor were they shown Brooks’s famous evidence to that committee in March 2003 when she said that her journalists had paid police for information in the past. Select committee evidence is not admissible in court because of rules around parliamentary privilege.

Beyond all that, the jury was specifically not invited to consider behaviour which may not be criminal but have most offended public opinion.

Breaking boundaries

As tabloid newspaper bosses, Brooks and Coulson ruined lives. They did it to sell newspapers, to please Murdoch, to advance their own careers. One flick of their editorial pen was enough to break the boundaries of privacy and of compassion. The singer’s mother suffering from depression; the actor stricken by the collapse of her marriage; the DJ in agony over his wife’s affair: none of their pain was anything more than human raw material to be processed and packaged and sold for profit. Especially, obsessively if it involved their sexual activity.

With all the intellectual focus of a masturbatory adolescent, their papers spied in the bedrooms of their targets, dragging out and humiliating anybody who dared to be gay or to have an affair or to engage in any kind of sexual activity beyond that approved by a Victorian missionary. They did it to friends – like Blunkett, for example, sharing drinks and private chats with him and then ripping the heart out of his private life, sprinkling their story with fiction as they did so. And to Sara Payne: befriended by Brooks in her campaign to change the law about publication of the home addresses of sex offenders; investigated by her paper on the false suspicion that she was having an affair with a detective.

But above all, they did it to their enemies. Among the politicians who they exposed for being gay or for having affairs, the leftwingers easily outnumbered the occasional stray rightwinger. In among them were the special enemies who dared to challenge News International. In the early stages of the hacking story, there was only one frontbench politician from any party who was willing to attack the News of the World – the Lib Dem home affairs spokesman Chris Huhne. In June 2010, when Brooks was chief executive of News International, it was her News of the World which exposed Huhne’s affair.

The News of the World also targeted the private life of its most outspoken critic in parliament – Tom Watson. Brooks had loathed Watson since he took part in the “curry house” plot in 2006, attempting to engineer Gordon Brown into Downing Street at the expense of her favourite, Tony Blair. News International reporters say that during the hacking saga, she called in reporters to ask if they had any dirt on Watson. The News of the World put a private investigator on his tail, hoping to catch him having an affair.

They did all this with breathtaking hypocrisy. While Coulson and Brooks were using their front pages to expose public figures for having affairs, they were themselves having an affair and keeping that information very private. Behind the scenes at the trial Brooks took the hypocrisy a step further. Although her newspapers had frequently attacked the Human Rights Act, she tried to use Article 6 – on the right to a fair hearing – to prevent her “affair” letter to Coulson being put before the jury.

Before the trial started, Laidlaw attempted to get the whole case against Brooks thrown out on the grounds that prejudicial newspaper coverage meant she could not get a fair trial. The crown replied by citing the case of Abu Hamza, who tried and failed to stop his own trial in 2006 because of prejudicial publicity in the Sun, then edited by Brooks. Laidlaw went on to complain about the scrum of press photographers waiting to pounce outside the Old Bailey door.

Power games

Their willingness to ruin lives was directly linked to their political power. MPs feared that they might find their own private behaviour being monstered on News International’s front pages. This is the power of the playground bully: he has only to beat up one or two children for all of them to start trying to placate him. Beyond that, government collectively feared having its agenda destroyed, its daily activity destabilised, its future terminated if Murdoch’s editors turned against it. Former ministers and senior Whitehall officials all tell the same tale – that as Murdoch increased the size of his empire, governments became obsessed with newspaper coverage, particularly that of the Sun.

The power which Coulson and Brooks enjoyed delivered the kind of access for which unscrupulous lobbyists will pay large bundles of cash. As a tabloid editor, she was courted by ministers. At the Leveson inquiry, Brooks disclosed 185 meetings with prime ministers, ministers and party leaders while apologising that her records were incomplete. At the News of the World, Coulson showed little enthusiasm for politics, according to former Downing Street officials, one of whom remembers him being invited for breakfast with Gordon Brown and showing so little interest in policy that the two men ended up talking about newspaper circulations. Brooks, however, was a different story.

Far more than Coulson, she played the game of power, exploiting her extraordinary social skills to build an unrivalled network of connections.

Backed by fear of what her journalists could do, Brooks used her access to get her way. She could do it over small things: “If she was going to the US and she realised she had no visa, all she had to do was to make a phone call to a minister, and they’d sort it out for her,” according to one former official. She used it to get stories. An adviser from the Ministry of Defence recalls the government being under pressure about British soldiers being killed and maimed by roadside bombs in Afghanistan: “We were told we couldn’t release all we were doing for opsec reasons, yet the MoD went ahead and gave the information to the Sun.”

More than that, she used her influence to try to change government policy, not simply and legitimately by publishing stories but privately with ministers by cajoling, insisting, playing on their fear. This might be aimed at scoring a victory for her newspapers – persuading the government to order a police review of the Madeleine McCann case as part of her strategy to encourage the toddler’s parents to let her newspapers serialise their book; pushing hard to end the career of Sharon Shoesmith, head of children’s services in Haringey, whom the Sun blamed for the death of Baby P. Shoesmith was sacked, a decision which was later described by the court of appeal as “intrinsically unlawful.” Or Brooks aimed at larger policy which suited the ideology of the Sun and of its owner – over crime, immigration, public spending and notoriously over Britain’s membership of the European Union and its potential involvement in the euro.

This exercise of power reached a peak with the sequence of events surrounding Murdoch’s attempt to buy BSkyB: the Sun turning on Gordon Brown in September 2009; the sustained campaign of hostile reporting apparently calculated to ensure that the electorate would force him out of office; the parallel campaign in all the Murdoch titles attacking the BBC and Ofcom; the announcement of the BSkyB bid within a month of David Cameron’s election; the Cameron government imposing drastic cuts on the BBC and Ofcom; Cameron’s culture secretary, Jeremy Hunt, allowing his special adviser to act as a back channel to the Murdochs while he considered the bid. Hunt duly gave a green light to the deal, which was within days of being confirmed in July 2011 when the hacking scandal erupted and moved parliament to denounce it.

Political distortion

And in all of this, Brooks consistently injected a highly contentious political ideology into the arteries of public debate, a toxic cocktail of crude populism and intellectual confusion. They demanded lower taxes and then damned public services for the failures inflicted on them by lack of funding. She led the cheers for stripping regulation out of the financial sector and then blamed Brussels for the ensuing crisis in the eurozone. She attacked the state when it inhibited corporate power and then promoted it when it engaged in military violence. She insisted on wars and then dared to claim to be the protectors of the soldiers who died in them (while Mulcaire, without her knowledge, hacked the phones of some of their families). She was a leader of opinion who had thought no further than the bland and self-serving simplicity of James Murdoch’s theory about free media, that the only guide to independence is profit.

As a single example of the distorting impact of their work, YouGov in December 2012, working for the TUC, found that the average public perception was that 41% of the welfare budget was spent on the unemployed. The reality is 3%. And that 27% of that budget was eaten up by fraud. The reality, as far as official figures can detect, is 0.7%. So the simple, beautiful idea of all citizens voting for government became an exercise in the bland leading the blind.

And while Operation Weeting succeeded in bringing cases to court, these "crimes" remain unchallenged. The power remains. Leveson’s attempt at independent media regulation was throttled at birth, not simply by the genuine concerns of those who care about a free press but also by a Fleet Street campaign of aggressive falsehood and distortion of precisely the kind that had made the Leveson inquiry necessary in the first place. Police officers resigned and politicians were embarrassed as the scandal erupted, but Scotland Yard – with dazzling cynicism – has reacted by trying to silence the kind of police whistleblowers who helped to expose the failures of their leaders; and ambitious politicians continue to dine with Rupert Murdoch. How long before News Corp’s famous summer party is revived as a compulsory opportunity for political genuflection?

It seems to have become forgotten, conveniently by some, that before the Old Bailey trial two former newsdesk executives, Greg Miskiw and James Weatherup, pleaded guilty, as did the phone-hacker Glenn Mulcaire and a former reporter, Dan Evans, who confessed to hacking Sienna Miller’s messages on Daniel Craig’s phone.

Neville Thurlbeck, the News of the World’s former chief reporter and news editor, pleaded guilty after the police found the tapes he had of Blunkett’s messages in a News International safe.

In the trial, Coulson was convicted of conspiring to hack phones while he was editor of the News of the World. The jury was discharged after failing to reach unanimous verdicts on two further charges of conspiring to commit misconduct in a public office faced by Coulson and Goodman.

But Brooks was found not guilty of four charges including conspiring to hack phones when she was editor of the News of the World and making corrupt payments to public officials when she was editor of the Sun. She was also cleared of two charges that she conspired with her former secretary and her husband to conceal evidence from police investigating phone hacking in 2011.

The jury at the Old Bailey returned true verdicts according to the evidence. They were not asked to do more.