Could the combination of

- the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights;

- the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights;

- the Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment;

- the Convention on Biological Diversity; and

- the Humanitarian Laws dealing with armed conflicts;

(for the purposes of this essay called Human Rights and Environment Obligations, HR & EO) be used to provide an adequate ethic for Aotearoa New Zealand investing agencies? [1]

This essay starts by defining and discussing the moral domain, with the three categories of everyday use of moral terms; schema such as codes of conduct; and key concepts or fundamental principles (metaethics). A brief history of ethical investing is described which includes the substitution of ethical for notions such as ESG and responsible. The inadequacies of these terms is provided (concept validity) and illustrated by comparing the New Zealand Superannuation Fund (NZSF) and the Norwegian Council of Ethics, and other evidence about banks and fossil fuels (construct validity).

The HR & EO are then described. Civil and Political Rights cannot be adequately observed without the exercise of Economic, Social and Cultural rights. Both sets of rights cannot be realised without the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, and the protection of the variety of living species on Earth – its biodiversity. Aotearoa New Zealand should include in the Bill of Rights the Conventions of Economic, Social and Cultural rights, and the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. It should ratify the Convention on Biological Diversity. These, with the Geneva Conventions, make up an integrated set of rights and obligations, that cover human-human and human-Earth relationships essential for humans to live with each other and within the capacity of the Earth to support human life.

However, for the HR & EO to be implemented, what is needed is the equivalent of national Animal Welfare Ethics Committees and relevant Codes of Conduct. Section 6 looks at some of the issues involved in applying environmental standards through such Committees. There are some international standards that are available for the application of the Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, and the Covenant on Biological Diversity. Other areas of the environment, such as the impact of eating meat, are more complicated, and involve a revaluing by society and a transition to an improved state. Others involve work to produce adequate standards.

The Auckland floods and the impact of Cyclone Gabrielle in 2023 has meant that many New Zealanders no longer deny climate warming and ecological degradation generally. But many have not acknowledged just how bad shape the environment is in, the threat of increasing extreme weather events in both regularity and intensity, and the increasing likelihood of the international community failing to mitigate these threats. Nor have they recognised the need to take the values they appreciate in their family and community settings and extend these to the economy and their investments. Aotearoa New Zealand is currently going down the wrong path. An HR & EO approach offers a way in which to take a better path and direction.

2 The Moral Domain

Values are judgements of worth. Some are personal preferences (example: I value my well-used crime novels) and others are adopted as public values when they are deemed necessary for the public good and its safety (example: murder is wrong). Public values are used to identify good or bad behaviour using rules. Standards are set in laws, codes of conduct, charters, creeds, cultural customs, and policies.

Moral language can be divided into three categories. In our everyday life, we use terms to identify worthy behaviour and character (rather than just personal preference) such as right, wrong, bad, good, duty, responsibility, respect, fairness, cooperation, gratitude, compassion, forgiveness, humility, courage, mutual aid, charity, trust, courtesy, integrity, avoiding harm, and loyalty. Included are not just judgements that deal with human-human behaviour but also human-Earth behaviour. One of the concepts that describes the special connection Māori have with the natural environment is te Taiao – a deep relationship of respect and reciprocity with the natural world. Another is kaitiakitanga - guardianship and sustainability.

A number of these terms are used in schema such as codes of conduct, laws, charters, creeds, and policies to describe acceptable behaviour in a variety of specific and general contexts, such as professions (examples: legal, medical) and organisations (examples: employer human relations policies; consumer rights). Examples of laws that incorporate values include the Human Rights Act, The Animal Welfare Act, the Wildlife Act, and the Bill of Rights Act.

Principles are fundamental truths or propositions that are the foundation for a system of belief or behaviour – see Table 1.

Metaethics explores the status, foundations, and scope of moral values, properties, and words.[2]It is often associated with ethical theories such as Aristotelianism, Utilitarianism or Consequentialism, and the Social Contract. This is where key principles and theories are advanced to explain what is right or wrong. Examples include Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia or flourishing; Bentham’s principle that actions are correct only if they ensure happiness and wrong or bad if they produce unhappiness; and Rousseau’s theory about defining the rights and duties of the ruled and their rulers. The categories of Everyday Level of Moral Language, Schema, and Metaethics together add up to the moral domain. [3]

The Social Contract with its promotion of rights was very influential leading to political reforms in France and America, and the production of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Another example of a metaethical debate leading to the adoption of laws is the writings of the consequentialist, Peter Singer, dealing with animal rights.[4] This followed on from the work of Bentham, the founder of the theory of utilitarianism. Singer also argued that animals can be in pain and distress and this was wrong when inflicted by humans. The principle, recognising the sentient nature of animals, has no international convention covering this (apart from the recent Convention on Biological Diversity), but thirty-two countries, including Aotearoa New Zealand, have formally recognised non-human animal sentience. These principles were incorporated in Aotearoa New Zealand legislation with the 1999 Animal Welfare Act, which stated that we cannot cause animals to suffer, to be in pain or distress. The Act enables the establishment of National Animal Welfare Ethics Committees, which describe Codes of Welfare that set minimum standards to the way in which persons care for animals and include recommendations on the best practice. The Code of Welfare for chickens for layer hens was reviewed in 2012, and farmers were given till the end of 2022 to change to more humane housing for chickens.

In the development of principles, codes, and their application, it is important that measures are validated. Validation is a term that establishes that a measure actually measures what it claims to measure. To establish that a measure of ethicality in investment is valid, both content and construct validity needs to be demonstrated. Content validity requires consideration at a conceptual level: does the measure make sense, and does it cover all the public values deemed necessary for our safety? Is or are the concept or concepts rich enough to capture the values in charters, laws, policies, and relevant policies? Construct validation requires empirical considerations: is the application of the measure consistent with other empirical evidence?

3 Ethical Investment

In the Western world prior to the Reformation, usury was a sin. However, this principle was not universal: Jews could loan to non-Jews; Christians could loan to non-Christians. Hence Christian Kings who wanted money for conducting wars, loaned from Jews. The change came with Calvin who allowed for the legitimacy of a 5% interest rate in particular business projects where no one's livelihood was endangered . But no loans at interest were to be charged to poor people who must borrow to live. The poor were to be protected. [5] This latter proviso has long been ignored by the financial and business community. Islam still adheres to an anti-usury principle. The Kiwisaver fund, Amanah, operates on Shari’ah Compliant principles. It has no investments in banks, particularly banks that invest in the fossil fuel industry.

The Methodists and The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) have long taken an ethical view towards money. In John Wesley’s 1757 sermon on the use of money, he said one should to provide for oneself and household. If you have an overplus still, as you have opportunity, do good unto all men. The Quakers started mid-seventeenth century and, because of persecution, created many business enterprises. They applied their testimonies of equality and justice in causes such as anti-slavery, equal rights for women, opposition to war, and their business enterprises, including the establishment of banks.

Since Calvin’s ruling, mainstream investment considered ethical investment a restriction on profitmaking. But roughly around the 1970’s and 1980’s opposition to apartheid, the Vietnam war, and a concern about the environment, led many investors to act on their beliefs.[6] A number of funds gradually started to develop ethical criteria. During that process, ethical investing was relabelled to eventually include the terms socially responsible investing; environmentally responsible investing; responsible investing; Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing; sustainable investing; values-based investing, impact investing, green investing; best-in-class investing; norms-based investing.[7] The Responsible Investment of Australasia (RIAA) stated that the responsible investment sector is hugely diverse and ethical investment cannot be defined. The establishment of the six principles of the United Nations Principles of Responsible Investment added to this confusion by not defining what responsible means. The ineffectiveness of this was recognised by one of the Co-Chairs of the Expert Group that drafted the United Nations Principles of Responsible Investment, who stated that the Responsible Investment community has not been more responsible than the investment community generally.

(T)he trillions of dollars controlled by RI asset owners, managers and consultants are not deployed consistent with long term investment strategies that would conduct our economies in a direction consistent with sustainable development, environmental protection, and greater economic justice – which would imply radical departures from what the market feels comfortable with and the valuation it puts on the large cap listed shares that dominate most global portfolios. [8]

The Reporting Exchange is an organisation that helps corporations disclose sustainability data, and tracks various ESG-related guidelines, such as regulations and standards. It reported that across the world the number grew from around 700 in 2009 to more than 1,700 in 2019. That includes more than 360 different ESG accounting standards.[9]

In 2021, Wise Response sent an Open Letter on the Ethics of Investment to the Prime Minister. The Letter identified five major problems:

▪ the values that guide the funds are usually not sufficiently comprehensive or wide-ranging to cover the social and environmental relationships in the ethical domain;

▪ the dominant international ESG framework (Environment, Social and Governance) is relatively weak, and often acts as a smokescreen for Business-As-Usual;

▪ the application of these so-called ethical frameworks is often flawed and far from transparent;

▪ the portfolios of all the KiwiSaver funds and the NZSF we reviewed contain banks listed among the 60 banks that invested a total of $3.8 trillion into fossil fuels from 2016–2020;

▪ the engagement and reporting practices of these funds are inadequate and lack transparency.[10]

The Letter was referred eventually to the Financial Markets Authority who replied that nothing could be done because values are subjective and constantly changing, a reply that should be a cause for concern about the competency of an important agency of Government. [11]

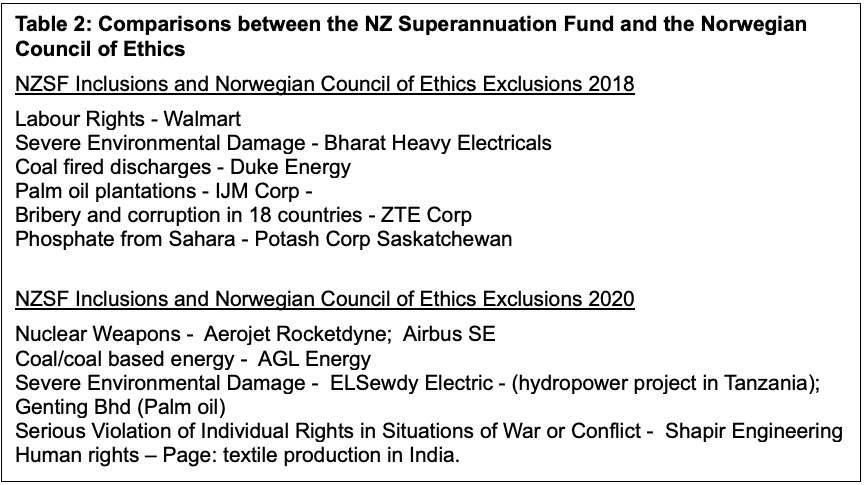

In the same year (2021) the Ministers of Finance and the ACC issued Enduring Letter of Expectations to Crown Financial Institutions in Relation to Responsible Investment. In a footnote it stated that For the purpose of this letter the terms ‘ethical investment’ and ‘responsible investment’ are interchangeable. [12] Responsible remains undefined in the letter or by the NZSF and the NZSF continues to invest in unethical companies. This is shown by comparing companies that Norwegian Council of Ethics has excluded, but the NZSF has included in its investment portfolios (Table 2).

In addition, in the five years since the Paris Agreement the NZSF has invested significantly in at least seven banks which have invested in fossil fuel companies even though they are primary drivers of climate heating. These include Citi, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley, Barclays, HSBC, Bank of Chinas, and Agricultural Bank of China. [13]

The NZSF in 2022 stated that responsibility is to be replaced by the notion of sustainable investment, on the grounds that this is the global direction of travel. The difficulty with the notion of sustainability is that there are weak and strong definitions. One meaning is to endure, to avoid the depletion of natural resources in order to maintain an existing ecological situation or balance. An ecological status quo or balance is inconsistent with the idea of evolution – change is inevitable. The goal is to ensure that any changes enable humans to continue to live. A weak definition does not recognise that the Earth is a closed system except for sunlight received, heat reflected into space, and external gravitational effects, and hence is based on unscientific premises. (This weak premise underlines the modern international economic system.) Hence it does not pass the content validity test.

In September 2022, NZSF reported that it has shifted about 40% of its overall investment portfolio to market indices that align with the Paris Agreement, the international climate change treaty. Unfortunately, how it claimed to achieve this is the MSCI World Climate Paris Aligned Index. The top ten Constituents includes JP Morgan Chase, which is the main investor in fossil fuels as identified by BankTrack. It should be noted that in 2016 the NZSF divested its direct investments in fossil fuels, but for strategic reasons, not on ethical principles.

The basic problem with the NZSF legislation is that their primary obligation is to invest on a prudent commercial basis in a manner that maximises returns and avoids prejudice to New Zealand’s reputation. The phrase avoiding prejudice to New Zealand’s reputation is so ineffective, that it needs to be changed to specify obligations to care for people and the planet. The legal advice NZSF sought soon after it was set up about smoking said that there was no conflict with its reputation, but the NZSF excluded it anyway. It also excluded Freeport-Moran over its mining in Indonesia. Both exclusions were because of public embarrassment. It should be noted that in 2016 the NZSF divested its direct investments in fossil fuels, but for strategic reasons, not on ethical principles. However, the evidence above showing investments in a range of unethical companies, and the problems with a 2050 target date (see comments below dealing with the Zero Carbon Act) in the Enduring Letter mean that the basic ethical clauses in the NZSF legislation need to be rewritten.

4 The Four Steps

There are four steps involved in ethical investing:

(1) define one’s values;

(2) exclude from investment where these values are not aligned, except when engagement is the tactical action chosen:

(3) engage with companies to change behaviour; and

(4) report on outcomes.

Step 1 involves choosing values that adequately cover both human-human and human-Earth components. Steps 2 and 3 involve choices between what types of investment to exclude and what companies to engage with to try and change behaviour. Step 4 involves reporting on outcomes.

Decisions about the second and third steps are tactical: some funds exclude a lot and others do not, and there is no single right approach. Divestment can lead to significant pressure on companies to change. And divestment is appropriate when a company’s values are in sharp conflict with a country’s values. Aotearoa New Zealand’s opposition to nuclear weapons is a good example. But divestment does not necessarily lead to a better outcome. Selling shares in a company to be bought by others who continue the business may make little difference. An example is where a number of the bigger fossil fuel companies are divesting parts of their activities, but many of these operations are being bought up by private equity or smaller companies in the petrochemical sector who are continuing business-as-usual. (This includes INEOS, a current sponsor of the All Blacks.) Hence it is better to engage with those companies to try and persuade them to change. A good example of a company that changed from a traditional fossil fuel company to a renewable energy company is Ørsted. [14] Divestment in their earlier mode of operation would not have supported their transition. But for companies that refuse to change, unpalatable options remain. It is hard to see Arab oil remaining in the ground.

Reporting, the fourth step, should enable an investor to know how closely the fund has followed its core value or values. If, for example, a fund has chosen the value of do no harm, then the reporting should clearly inform an investor how the investments in that fund have done no harm, or from actions and engagement whether there has been any change to achieve that aim in the future.

5 Human Rights, International Humanitarian Law, and Environment Obligations

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1948, setting forth general rights, with covenants containing binding commitments to be subsequently developed. This task was divided into two: Civil and Political Rights, and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Both Covenants were adopted at the UN General Assembly in 1966. Aotearoa New Zealand ratified both Covenants in 1978.

The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 affirmed Aotearoa New Zealand’s commitment to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. These include life and security of the person (example: right not to be deprived of life); democratic and civil rights (example: electoral rights); non-discrimination and minority rights; search, arrest and detention (example: rights of persons arrested or detained). The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 did not include any rights under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. This Covenant includes the following: right to adequate food: Right to adequate housing: right to education: right to health: right to social security: right to participate in cultural life: right to water and sanitation: right to work, rights in work and the right to form trade unions and to strike.

In 1948 Colin Aikman, on behalf of Prime Minister Peter Fraser, stated that

Experience in New Zealand has taught us that the assertion of the right of personal freedom is incomplete unless it is related to the social and economic rights of the common man. There can be no difference of opinion as to the tyranny of privation and want. There is no dictator more terrible than hunger. … These social and economic rights can give the individual the normal conditions of life which make for larger freedom, And in New Zealand we accept that it is the function of government to promote their realisation. [15]

On July 28, 2022 the UN General Assembly declared that it is human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. The substantive elements include clean air; a safe and stable climate; access to safe water and adequate sanitation; healthy and sustainably produced food; non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play; and healthy biodiversity and ecosystems. [16] There were 161 votes in favour, no votes against, and 8 abstentions. Prior to the July 2022 vote, the right to a healthy environment was legally recognised in more than 80% of UN Member States (156 out of 193 States). Aotearoa New Zealand was in the 20% of countries that had not recognised the right to a healthy environment. While it supported the July 2022 vote, it has not yet ratified this right.

The historical background to this started in 1972, when the UN held its first global environmental conference in Stockholm. States adopted the first principle which states that people have the fundamental right to freedom, equality and adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being. Throughout the 1970s, the right to a healthy environment began appearing in national and regional constitutions throughout the world.

In 2022 the Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity was held in Montreal, Canada. This led to the international agreement to protect 30% of land and oceans by 2030 (30 by 30) and the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. [17] Biodiversity refers to the variety of living species on Earth, including plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi.[18] The five major drivers of loss of biodiversity are invasive species; changes in land and sea use; climate change; pollution; direct exploitation of natural resources. [19]

A major part of international humanitarian law is contained in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949. The Geneva Conventions specifically protect people who are not taking part in the hostilities (civilians, health workers and aid workers) and those who are no longer participating in the hostilities, such as wounded, sick and shipwrecked soldiers and prisoners of war. The Conventions have been developed and supplemented by two further agreements: the Additional Protocols of 1977 relating to the protection of victims of armed conflicts. Other agreements prohibit the use of certain weapons and military tactics and protect certain categories of people and goods. These agreements include: the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, plus its two protocols; the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention; the 1980 Conventional Weapons Convention and its five protocols; the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention; the 1997 Ottawa Convention on anti-personnel mines; the 2000 Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict. Geneva Conventions need to be included because, while civil and political rights assert there is a right to life, war with loss of life is an unfortunate reality, and there need to be rules about behaviour in conflict areas. Aotearoa New Zealand has ratified these Conventions. There are companies who breach these that the NZSF had invested in (Table 2).

Civil and Political Rights cannot be adequately recognised without the exercise of Economic, Social and Cultural rights. Both sets of rights cannot be realised without the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, and the protection of the variety of living species on Earth – its biodiversity. Aotearoa New Zealand should include in the Bill of Rights the Conventions of Economic, Social and Cultural rights, and the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. It should ratify the Convention on Biological Diversity. These, with the Geneva Conventions, make up an integrated set of rights and obligations, that cover human-human and human-Earth relationships essential for humans to live with each other and within the capacity of the Earth to support human life.

Can the HR & EO adequately cover the moral domain to provide a validated ethic for investing agencies? The HR & EO are at a broad level and need further elaboration for implementation. One way around this is to add to the HR& EO, a requirement to observe other fundamental UN Treaties, ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand. And to set up an Ethics Committee (following the Animal Welfare Act model) to require that an Ethics Committee to also consider other appropriate conventions and treaties that Aotearoa New Zealand has ratified, and international standards such as CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

These Committees should be required to develop Codes that take into account particular features of a sector, such as the Code for chickens including the provision of cages that permit adequate space for moving. In the investment sector, codes should permit the ability for agencies to engage with companies they are invested in, to persuade them to change. Codes for business should include rules for good governance, fair benefits and rewards of the organisation’s activity to all stakeholders, and financial and ethical integrity and transparency. These principles can be derived from and consistent with the higher order rights and obligations described in the HR & EO.

Aotearoa New Zealand has signed up to more than 1900 international treaties, [20] These include free trade agreements, military alliances, and many of a technical nature (example: Geneva Convention on Road Traffic) that are not relevant here. Some are, such as Chemical Weapons Convention and Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty.

On the Department of Conservation website is a list of the international and multinational Conventions and Agreements that Aotearoa New Zealand has signed up to. These include the

- Antarctic Treaty System,

- the Convention on Biological Diversity,

- the Convention in International Trade in Endangered Species,

- International Union for Conservation of Nature,

- The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species,

- Pacific Regional Environmental Programme,

- Ramsar Convention on Wetlands,

- the International Whaling Commission,

- the World Heritage Convention,

- Basel Convention,

- London Convention,

- MARPOL,

- UN Convention on the Law of the Seas,

- UNFCCC,

- Vienna Convention on the Protection of the Ozone Layer. [21]

In 2010, Grant Robertson, then in opposition, spoke to a private member’s bill proposed by Marian Street: Ethical Investment (Crown Financial Institutions) Bill. [22] That bill referred to the following examples of international norms, treaties, and conventions.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948:

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights:

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights:

- International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination:

- Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women:

- Convention on the Rights of the Child:

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment:

- Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (1998) – ILO:

- Tripartite Declaration of Principles Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (1997) – ILO:

- Guidelines for Multinational Enterprise (1997, 2000) – OECD:

- Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights:

- UN Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with regard to Human Rights – UN:

- CHR resolution 2005/69 – UN:

- Environmental Treaties covering Agriculture, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Conservation, Environment, Fisheries and Trade.

The Bill did not proceed because the National Government said that the market forces organisations to act in a way that is respectful of what the public would demand. [23] Despite promoting this Bill, Robertson took no action when Labour had a majority in the House between 2020-2023.

Some of the issues involved in the use of treaties and standards in Codes of Conduct is illustrated in the next section, dealing with the environment right.

6 Implementation of the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and the obligation to protect biodiversity.

If consideration is given to whether a company is worth investing in because it meets the environmental right (regarding clean air; a safe and stable climate; access to safe water and adequate sanitation; healthy and sustainably produced food; non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play; and healthy biodiversity and ecosystems) it is necessary to establish standards that can be used to make these assessments.

From the human-Earth perspective the analysis can be divided into

a) human-Earth relations overall;

b) human-animal relations (includes cattle, fish, birds);

c) human-other life forms relations;

c1) plants and forests;

c2) rivers, lakes, and oceans;

c3) atmosphere.

6.1 Overall – ecological footprints

Currently humans are not living within the means of our planet's resources. The world's ecological footprint currently is 1.7 global hectares. The New Zealand footprint is 4.3 global hectares so we are living 2.5 times beyond our ecological footprint. Do the Human Rights cover this? Yes - living beyond the capacity of the Earth to support human life is not consistent with healthy biodiversity and ecosystems.

6.2 Animals, fish, and birds

Is eating animals and fish and birds, unethical? Peter Singer, in his book Animal Liberation [24] argues on utilitarian grounds against eating meat. He states that the boundary between species is arbitrary when one considers the great apes who surpass some humans in their capacities. (Some philosophers add dolphins and call them both living nonhuman persons.) Singer showed that the widespread agricultural industrial practices at that time took no account of animal suffering, and that much of animal experimentation caused unnecessary pain and in a number of cases contributed little to advancing scientific knowledge.

Regarding fish, Culum Brown from MacQuarie University [25] states that fish are more intelligent than they appear. Their cognitive powers match or exceed those of higher vertebrates including non-human primates. Singer quotes a 1976 inquiry by the British Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals: they concluded that the evidence for pain in fish is as strong as the evidence for pain in other vertebrate animals. For other forms of marine life, the evidence that they have a capacity for pain is less clear. Singer suggests drawing the line between a shrimp and an oyster, although he continued to occasionally eat oysters, scallops, and mussels after he became a vegetarian.

Singer and other individuals and organisations advocating for animals have been successful in moving the public to accept that animals experience pain and are therefore entitled to proper care. This has led to a reduction of animal experimentation, but not in industrial agriculture with its continued harmful living conditions and treatment of animals. The main arguments used by Singer are based on animal abuse. He acknowledges that this does not, logically, prohibit animals who have lived free of all suffering and have been instantly and painlessly slaughtered. But he states that practically and psychologically it is impossible to be consistent in one’s concern for nonhuman animals while continuing to dine on them.

According to Rachel Graham meat production accounts for 57 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions of the entire food production industry. It also results in widespread deforestation and loss of biodiversity, and each of these means that it significantly contributes to climate change. This is especially true of meat production from factory farming operations.[26] Humpenoder et al have shown that a flexitarian diet could lower methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture and lower the impacts of food production on water, nitrogen, and biodiversity. This in turn could reduce the economic costs related to human health and ecosystem degradation and cut GHG emissions pricing, or what it costs to mitigate carbon, by 43% in 2050. [27]

If a Fund does not include in its exclusions companies that are involved in the production of meat, is it unethical? Switching to a meat free economy in Aotearoa New Zealand without major social disruption, would be impossible in the short term. There is a trend towards a greater number of New Zealanders becoming vegetarian. Investment in companies where they encourage a flexitarian approach (people who have a primarily vegetarian diet but occasionally eat meat or fish) with assistance for a government programme for the transition to diversification for meat producers is morally acceptable. Similar arguments can be applied to the question of eating fish.

6.3 Land and soils, plants and forests

Regarding land and soils, ISRIC – World Soil Information - is an independent foundation with a mission to serve the international community as a custodian of global soil information. They support soil data, information and knowledge provisioning at global, national and sub-national levels for application into sustainable management of soil and land. New Zealand’s Ministry for the Environment has standards for assessing and managing contaminants in soils to protect human health.

Regarding human-other life forms, it is not unethical to eat plants and cut trees for homes. We can harm plants but usually the reason is due to wastefulness, or carelessness. However, when it comes to endangered species, and biological diversity, Aotearoa New Zealand has signed up to international conventions where species survival is threatened: CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

We do place value on particular trees, such as Tane Mahuta, and other trees that are special for cultural or historic reasons. We give priority to indigenous as opposed to introduced trees and plants. But it is stretching it too much say that eating plants and cutting trees for making homes is immoral. Permitting the use of plants and trees for human utility, but excluding individual trees and tree types on grounds that incorporate cultural and historical factors and preference is given to indigenous species should be acceptable.

We can say, however, that using the term to include plant and forest ecosystems (like harming the Amazon forests by chopping them down for replacement by palm trees) is immoral.

According to Ruis and Sotirov et al [28] many existing international treaties contain provisions that aim to regulate certain activities related to forests. However, there is no global legal instrument in which forests are the main subject; there is no international treaty in which all environmental, social and economic aspects of forest ecosystems are included, and political trends suggest that such a treaty will not be created in the foreseeable future.

The Forest Stewardship Council claims that its certification is internationally recognised as the most rigorous environmental and social standard for responsible forest management. [29] But FSC-Watch was formed because of the unreliability of the certification. [30] The founders of FSC-Watch include Chris Lang who looked critically at the FSC certification process in Thailand, Laos, Brazil, USA, New Zealand, South Africa, and Uganda, and found serious problems in each case. They assert that the governance and control of the FSC has been increasingly captured by vested commercial interest.

However, the standards themselves are not under question. In particular, Principle 3 (Indigenous People’s Rights); Principle 4 (Community Relations); Principle 5 (Benefits from the forest); and Principle 6 (Environmental Values and Impacts), are relevant to Human Rights standards.

Standards New Zealand have published the New Zealand Standard Sustainable Forest Management. [31] The Standards say that their report is intended to be compatible with relevant international and national policy instruments, and has been developed with national and international audiences in mind, as well as for implementation by forest managers in a local or regional setting.

Do the HE & EO capture the moral responsibilities towards forest and plants? The short answer is a qualified, Yes. At an individual level it is ethical to use plants and trees for human utility, except where individual trees and tree types are protected on grounds that incorporate cultural and historical factors and preference is given to indigenous species. At a collective level, if forest behaviour does not accord with the standards of the Forest Stewardship Council, and in particular Principles 3, 4, 5 and 6 (leaving aside the issues of monitoring and auditing those standards), or an equivalent or better set of standards, then the behaviour is unethical.

From the aspect of human-other life forms relations, Human Rights can be content validated if it is understood at least as incorporating reference to CITES, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and to the key principles of human-forest behaviour of the Forest Stewardship Council, or an equivalent or better set of standards, and recognising the need to protect plants and trees on cultural and historical factors, and preference given to indigenous species.

6.4 Rivers, lakes and oceans

There is plenty of harm done to many if not most of the world’s rivers, lakes and oceans, according to Oceana. [32]They identify the following major problems;

- We are taking too many fish out of the water;

- We are polluting our oceans with mercury, oil, and climate changing gases;

- We are trashing marine wild life and special places;

- Destructive and wasteful fishing practices threaten animals and damage the sea floor.

We know that are waters are in poor shape – threatened by pollution including damage from plastics, over fishing and destructive fishing practices, and sediment erosion.

The Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 reported on progress to the 20 Aichi biodiversity Targets agreed in 2010. The Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 found that despite progress in some areas, natural habitats have continued to disappear, vast numbers of species remain threatened by extinction from human activities, and $500bn (£388bn) of environmentally damaging government subsidies have not been eliminated . The targets were based on the Convention on Biological Diversity, which HR & EO Aotearoa New Zealand has adopted, and describes the standards and processes that each country should adopt in the conservation and protection of biodiversity . Fresh water and oceans are included . The Convention on Biological Diversity relies on individual countries for the implementation of its standards.

However, according to Dr Mike Joy

there is no one measure that will cover everything. (M)ost developed countries use some forms of biomonitoring to assess health, but these are by necessity regional. There are many limits for chemicals, thousands of them and they vary hugely and are often based on guesses because they likely interact with each other. The only thing close to an international measure is nitrate concentration. There is an international drinking water limit of around 11 ppm, (but China has less than 1ppm standard) but the ecosystem health protection level is around 1 ppm and many countries work on that EU, some US states etc. In NZ the Science technical advisory group said 1ppm and the minster chose 2.4 ppm. The required steps depend on the drivers and vary everywhere. [33]

Professor Simon Thrush states that standards do

exist for specific contaminants but some of the major stressors in our ecosystems do not have adequate standards, Standards are not currently designed to deal with cumulative effects and they work poorly when dealing with non-linear change... These (well almost all) ecosystems are connected and yet we currently manage them in a disconnected way. Our Fresh Water standards do not deal well with our estuaries and coasts. …There are EU frameworks such as the Water Framework Directive and the Marine strategy, but these are all implemented slightly differently by the member states. [34]

Despite the absence of international standards, an ethical company will measure and report on its ecological impact on rivers, lakes and oceans, and waste that it puts into them, using the best available regional standards available based on modern science, and take into account international reports, such as those based on the Convention of Biodiversity. It will also account for any production and use of chemicals, to ensure that they are not harmful. When appropriate the precautionary principle will be followed.[35]

6.5 Atmosphere

The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that the 2005 WHO Air Quality Guidelines offer global guidance on thresholds and limits for key air pollutants that pose health risks. The Guidelines indicate that by reducing particulate matter (PM10) pollution from 70 to 20 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m), we can cut air pollution-related deaths by around 15%. The Guidelines apply worldwide and are based on expert evaluation of current scientific evidence for particulate matter (PM); ozone (O3); nitrogen dioxide (NO2); and sulphur dioxide (SO2).[36]

In addition to WHO Air Quality Guidelines, needs to be added the matter of climate warming. The evidence that the climate is warming is overwhelming accepted by the scientific community that no further justification is required here. The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures is the best practice internationally for disclosure on climate-related financial information.[37]

The above review of standards show that there are some international standards that are available for the application of the Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment and the protection of biodiversity. Other areas of the environment, such as the impact of eating meat, are more complicated, and involve a revaluing by society and a transition to an improved state. Others involve work to produce adequate standards.

It might be argued that this is imposing addition effort and cost on companies and the agencies involved in their support. This ignores what currently happens. In The Health and Safety Guide for Directors it states that “The governance of an organisation involves a framework of values, processes, and practices. Through this framework, directors and boards exercise their governing authority and make decisions to achieve the organisation’s purpose and goals. Directors ensure the organisation operates ethically and complies with all laws and regulations.”

There are companies that accept this responsibility, but others who do only the bare minimum. One of the better is Wesfarmers, which operates Bunnings in New Zealand. Their Annual Report 2020 states:

“While we are very clear that providing satisfactory returns to our shareholders is our primary purpose, we have always qualified that by pointing out that we could never achieve that objective over the long term if we did not protect and enhance the interests of our other stakeholders – our team members, customers and suppliers – and if we did not take care of the environment or support the communities in which we operate.”

In their Sustainability Report they state:

“We recognise that in a world with finite natural resources, the traditional ‘linear’ business model that relies on a take-make-waste extractive industrial approach is not sustainable in the long term. Over the last 18 months, our businesses have worked to develop a circular economy strategy. In some divisions this has involved the development and use of advanced life-cycle assessment models to evaluate and prioritise the environmental impacts of products over their life-cycle, along with customer insights and detailed materials studies using leading global specialists. At Kmart and Target, these activities have confirmed plastic, polyester, cotton, wood, chemical use, water impacts, packaging, greenhouse gas and waste diversion as priorities.”

7 Conclusion

The Briefing to the Incoming Minister for Emergency Management and Recovery states that severe weather events, exacerbated by climate change, are the new normal.[38] The Ministry for the Environment states that scientists globally agree that climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, and that those impacts will continue to worsen in the future.[39]

The previous Labour Government set up a Zero Carbon Act. [40] Aotearoa New Zealand’s First Emission Reduction Plan and Aotearoa New Zealand’s First Adaptation Plan followed in May and August 2022 respectively. Carbon Action Tracker (CAT) provided an assessment of Highly Insufficient to these efforts to date.[41] One of the reasons for this is the heavy reliance on the proportion of its target (two thirds of the action required) through buying international offsets. Professor Ilan Noy, Chair in the Economics of Disasters and Climate Change at Victoria University, makes many similar criticisms, and further points out the heavy reliance on offsets by many developed countries.[42] The plan to reduce emissions using offsets will be very expensive and likely unsuccessful.

A further problem is that in the Zero Carbon Act is the date for the accomplishment of the reduction of emissions – 2050. This timeline does not consider that the world is likely to reach 1.5 much earlier. James Hansen et al has stated: under the current geopolitical approach to GHG emissions, global warming will likely pierce the 1.5°C ceiling in the 2020s and 2°C before 2050. [43] Regardless of the accuracy of the predictions, actual events are showing widespread severe weather events and their destruction are occurring much faster. Copernicus, an EU Climate Change Service, has stated that 2023 was the warmest year on record, close to 1.5°C above pre-industrial level. [44]

If the world is to successfully face the environmental challenges posed by climate warming and loss of biodiversity, the way we invest needs to change. According to Accenture, a consultancy, around one-third of the world’s 2,000 biggest firms by revenue now have publicly stated net-zero goals. Of those, however, 93% have no chance of achieving their targets without doing much more than they are now. Few businesses lay out credible investment plans or specify milestones against which progress can be judged. [45]

Unfortunately, the principles used to guide investment, such as responsible investment, are invalid in that the application of these principles does not include companies that fully care for people and the planet, and exclude companies that harm people and destroy the planet and its ecosystems essential for life, including human life, on earth.

MacIntyre argues that in any critique of the philosophical theories claiming to identify how to describe what a good life is, and the transition to it, must consider the disability and dependence on others that all of us experience at times during our lives. How this is carried out is in the interest of the whole political society, that is integral to an understanding of the common good. He is sceptical about the behaviour of modern nation-states because they are governed through a series of compromises between a range of conflicting economic and social interests. [46] To this understanding of the common good must be added care for the environment.

For the last forty or so years, Aotearoa New Zealand has wavered between a libertarian ideology that favours markets over government in the supply and regulation of goods and services, and governments that have attempted to follow the responsibility described by Aikman and Fraser quoted above. There is considerable literature about the conflict with science (laws of thermodynamics) and ethics (promotion of self-interest and exploitation of the environment) with a libertarian ideology [47] but the wealthy elite pursue a self-interest that ignores this evidence. Two Aotearoa New Zealand examples and a statement from the new Minister for Oceans and Fisheries, Regional Development, Resources, Associate Minister of Finance, and Associate Minister for Energy illustrate the ideology’s inadequacies.

The privatisation of Telecom resulted in a significant loss to the company’s assets, and to the considerable enrichment of overseas owners (Bell Atlantic and Ameritech) and local bankers and advisors (Fay, Richwhite, Gibbs and Farmer).[48] Brian Gaynor calls it a "me first" concept. This is where the interests of the major controlling shareholder, who usually has a short-term horizon, are given priority. Under this approach a company is heavily reliant on debt, has a high dividend payout policy, large directors' fees, generous golden handshakes, and a strong emphasis on capital repayments. [49] Other stakeholders and the common good is ignored.

The leaky homes crisis concerned timber-framed homes built from 1988 to 2004 that were not fully weather-tight because of a change in the building code, the elimination of building apprentice schemes, and the closure of government-run technical training bodies resulting in significant de-skilling of builders. The consequences often included the decay of timber framing which, in extreme cases, made buildings structurally unsound. The saga has been labelled Aotearoa New Zealand's largest man-made disaster. One report put the number of homes with issues at a conservative 174,000, at a cost to the country of around $47 billion.[50]

Minister Shane Jones said that if a frog stood in the way of a mine, it was "goodbye, Freddy".[51] He promised common sense, slammed "dreamy", "fairy-tale" climate goals and said power cuts would not be happening under his government’s watch. He also indicated they would take a blowtorch to the review of stewardship land. The coalition was going to bring "rigour and common sense to the hysteria surrounding climate change". "Mining is coming back as well. We most certainly need those rare earth minerals." [52]

The world and Aotearoa New Zealand has arrived at the stage where mitigation alone is insufficient: adaptation is also required, which will be substantial and difficult. We face moral choices where at one end wealthy elites who are the world’s top 1% of emitters produce over 1000 times more CO2 than the bottom 1%.[53] Many wealthy people have prepared bolt holes from the ecological and economic destruction that they see coming (and are substantially responsible for).[54] At the other end are people who accept the need for an ethic that cares for people and the planet, and is based on human rights, environment obligations, and the common good. Aotearoa New Zealand is currently trucking down the wrong path.

Perhaps the final words should be left to Martha Nussbaum, writing in her book, Political Emotions. Why Love Matters for Justice.

In the type of liberal society that aspires to justice and equal opportunity for all, there are two tasks for the political cultivation of emotion. One is to engender and sustain strong commitment to worthy projects that require effort and sacrifice – such a social redistribution, the full inclusion of previously excluded or marginalized groups, the protection of the environment, foreign aid, and the national defense. Most people tend towards narrowness of sympathy. They can easily become immured in narcissistic projects and forget the needs of those outside their narrow circle. Emotions directed at the nation and its goals are frequently of great help in getting people to think larger thoughts and recommit themselves to a larger common good. [55]

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Margaret Bedggood for helping direct me to relevant legal matters and discussion of these.

[1] The boundaries between the two categories, human-human and human-Earth relationships, are becoming more blurred. The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment contributes to this, with the substantive components of clean air; a safe and stable climate; access to safe water and adequate sanitation; healthy and sustainably produced food; non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play; and healthy biodiversity and ecosystems, being defined as a human right. It is probable that animal rights, for example, could be derived from this list, but to avoid doubt, the Convention on Biological Diversity is included in the HR & EO category.

[2] Metaethics. Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://iep.utm.edu/metaethi/

[3] A description of the interrelationship between ethics, economics and science is contained in a) and pictured in b)

- How we are to live?Fabians, March 2015 Retrieved from

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1wWx87wbcF5wITYfMz9wNbgqtJd_XX67m/view?usp=drivesdk

- Wiring Diagram. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1TM59O2YuJFKzAMGDWHh5rnOmaXpZU_oh/view?usp=drivesdk

[4] Singer, P. 1975 Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for our Treatment of Animals, New York Review/Random House, New York.

[5] McKee, E A. The Character and Significance of John Calvin’s Teaching on Social and Economic Issues. In Dommen, E and J D Bratt ed. (2007) John Calvin Rediscovered. Westminster John Knox Press 2007.

[6] Sparkes, R. 2022. Socially Responsible Investment. A Global Revolution. John Wiley & Sons.

[7] Howell, R. 2017. Investing in People and the Planet. ISBN 978-0-473-38418-0

[8] Joly C 2012 Reality and Potential Responsible Investment in Responsible Investment in Times of Turmoil. Ed Vandekerckove w, et al Dordrecht: Springer

[9] Economist. 3 Oct 2020. The proliferation of sustainability accounting standards comes with costs. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/business/2020/10/03/the-proliferation-of-sustainability-accountingstandards-comes-with-cost

[10] Wise Response. Retrieved from https://wiseresponse.org.nz/2021/10/21/open-letter-to-prime-minister-on-the-ethics-of-investment/#:~:text=Open%20Letter%20to%20Prime%20Minister%20on%20the%20Ethics,The%20letter%20is%20available%20as%20a%20PDF%20here.

[11] FMA Disclosure framework for integrated financial products. Retrieved from

https://www.fma.govt.nz/assets/Guidance/Disclosure-framework-for-integrated-financial-products.pdf

[12] Ministers of Finance and ACC. Enduring letter of expectations to crown financial institutions in

Relation to responsible investment Retrieved from https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021

[13] BankTrack. 2021. ‘Banking on Climate Chaos’. Retrieved from https://www.ran.org/bankingonclimatechaos2021/#score-panel.

[14] Ørsted. Retrieved from https://orsted.com/en/who-we-are/our-purpose/our-green-energy-transformation

[15] Tong, D. 3 August 2023. The case for including ESC rights in NZBORA. Retrieved from https://humanrights.co.nz/2023/08/03/the-case-for-including-esc-rights-in-nzbora/

[16] https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-01/UNDP-UNEP-UNHCHR-What-is-the-Right-to-a-Healthy-Environment.pdf

[17] Retrieved from https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf

[18] National Geographic. Retrieved from https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/biodiversity/

[19] Five drivers of the nature crisis. UNEP. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/five-drivers-nature-crisis

[20] NZ Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved from https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/about-us/who-we-are/treaties/

[21] Ministry for the Environment. New Zealand’s international obligations. Retrieved from

[22] Ethical Investment (Crown Financial Institutions) Bill. Retrieved from

https://www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/member/2010/0149/5.0/whole.html

[23] Ethical Investment (Crown Financial Institutions) Bill — First Reading 2010. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/49HansD_20100804_00000932/ethical-investment-crown-financial-institutions-bill

[24] Singer, P. 1975 Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for our Treatment of Animals, New York Review/Random House, New York.

[25] Macquarie University. Retrieved from https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/persons/culum-brown

[26] Graham, R. Dec 21 2022. Why Is Eating Meat Bad For the Environment and Climate Change? Retrieved from https://sentientmedia.org/why-is-eating-meat-bad-for-the-environment/

[27] Humpenoder, F et al. Science Advances 27 Mar 2024 Vol 10, Issue 13 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adj3832

Retrieved from https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adj3832

[28] Part of the problem for the human-other life regarding forests is the lack of adequate international treaties. See International Forest Governance and Policy: Institutional Architecture and Pathways of Influence, in Global Sustainability by Sotirov et al (Sustainability 2020, 12, 7010; doi:10.3390/su12177010).

[29] Forest Stewardship Council. Retrieved from https://fsc.org/en/document-centre/documents/resource/392

[30] FSC-Watch. Retrieved from https://fsc-watch.com/about/

[31] Standards New Zealand. NZS AS 4708:2014

[32] Oceana. Retrieved from https://oceana.org/what-we-do

[33] Personal Communication. Senior Research Fellow, School of Government, Victoria University.

[34] Personal Communication. Head of Institute of Marine Science, Auckland University.

[35] Precautionary Principle. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/precautionary-principle

[36] World Health Organisation. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health

[37] Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Retrieved from https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf

[38] Briefing to the Incoming Minister for Emergency Management and Recovery https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2024-02/bim-2023-nema.pdf

[39] Ministry for the Environment. Feb 2023. The science linking extreme weather and climate change.

[40] Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019. Retrieved from https://environment.govt.nz/news/the-science-linking-extreme-weather-and-climate-change/ https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2019/0061/latest/LMS183736.html

[41] Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved from https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/new-zealand/

[42] Noy, I 2023. What would NZ look like in a 1.5 - 2+ degree Celsius world, from an economic perspective? Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Cqk2P_Dkaw&t=1425s

[43] Hansen, J et al. May 2023. Global warming in the pipeline. Retrieved from

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.04474

[44] Copernicus. Retrieved from https://climate.copernicus.eu/global-climate-highlights-2023

[45] Economist Nov 10th 2022. The UN takes on corporate greenwashing. Available at https://www.economist.com/business/2022/11/10/the-un-takes-on-corporate-greenwashing

[46] MacIntyre A. 1999. Dependent Rational Animals. Why Human Beings Need the Virtues. Open Court Publishing Cpy

[47] In 1992 some 1,700 of the world's leading scientists, including the majority of Nobel laureates in the sciences, issued the World Scientists' Warning to Humanity. The scientists state that the earth is finite. Its ability to absorb wastes and destructive effluent is finite. Its ability to provide food and energy is finite. Its ability to provide for growing numbers of people is finite. And we are fast approaching many of the earth's limits. Current economic practices which damage the environment, in both developed and underdeveloped nations, cannot be continued without the risk that vital global systems will be damaged beyond repair. A new ethic is required – a new attitude towards discharging our responsibility for caring for ourselves and for the earth. Retrieved from https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/1992-world-scientists-warning-humanity

[48] Telecom jackpot: How privatisation made fortunes. NZ Herald. Retrieved from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/telecom-jackpot-how-privatisation-made-fortunes/UZDCEVRGWCB3S7XOFTFUNS3VK4/

[49] <i>Gaynor:</i> Icon businesses stripped by greed. NZ Herald. Retrieved from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/igaynori-icon-businesses-stripped-by-greed/YJIAVQZH75JV5BOE5NL2HW3Y4E/

[50] The 'Rottenomics' of the $47 billion leaky homes market failure. Rob Stock. Retrieved from https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/116236850/the-rottenomics-of-the-47-billion-leaky-homes-market-failure

[51] Retrieved from https://www.odt.co.nz/regions/west-coast/goodbye-minister-tells-frogs-impeding-mining

[52] One of the problems with mining and fossil fuel exploration is they leave a mess for the Government to clean up. If mining is to go ahead, one way is to ensure that they clean up their mess is require a bond to be paid up front by directors and other officers of mining companies, related processing companies, and similar types of companies, to fund rehabilitation of the environment when the company ceases its operations or goes bankrupt, similar to the arrangements that Waihi Gold Mines are presently required to carry out.

[53] Cozzi L, O Chen, K Hyeji. The world’s top 1% of emitters produce over 1000 times more CO2 than the bottom 1%. Feb 2023. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-world-s-top-1-of-emitters-produce-over-1000-times-more-co2-than-the-bottom-1

[54] Survival of the Richest. Rushkoff, D. 2022. Scribe.

[55] Nussbaum, M. 2013. Political Emotions. Why Love Matters for Justice. HUP